This dish brings back some of my fondest childhood food memories. Calzone di cipolla, or onion pie, is one of the signature dishes of the cuisine of Puglia. My grandfather Lorenzo hailed from a small town outside of Bari, the capital of Puglia, called Grumo Appula. His sister, whom we called Zia Angelina (not to be confused with my grandmother and her sister-in-law Angelina) made this pie her specialty. It has been years since I had last tasted this dish and had lost track of Zia Angelina's recipe, but, as luck would have it, a friend of the family named Maria Savino, also from Grumo Appula, provided us with the following recipe:

Spread the sautéed onion mixture in a 23 cm/9-inch pie or quiche pan lined with a crust of your choice (see Notes for details on different crusts to use). Arrange some black olives and anchovy fillets, roughly chopped if you like, evenly on top of the onions. You should use enough so that every bite will have a bit of olive and a bit of anchovy. Cover the pie with another round of crust, pinch the bottom and top crusts together and then either trim off the edges (as in the photo above) or fold the extra bit of crust inwards to make a nice border. Make slits in the top crust to allow air to escape. (If you prefer, you can also simply prick some holes in the crust.)

Bake the calzone in a moderately hot oven (180° C, 375° F) for about 30-45 minutes, or until the crust is nicely browned and the pie is giving off a wonderfully savory aroma. Allow the pie to cool before serving. You can eat it warm (not hot) but, to my taste, the pie is much better at room temperature—and it tastes even better the day after you make it.

NOTES: Like any classic, there are any number of possible variations to this dish. There are variations in the onion filling: Zia Angelina's recipe called for a bit of tomato sauce instead of fresh tomatoes, plus a sprinkling of oregano. Other recipes omit the tomatoes altogether and call for adding grated pecorino cheese, raisins softened in warm water, bread crumbs and/or capers. Some recipes allow or call for green olives rather than black. The recipe for a version of this dish contained in Maria Pignatelli Ferrante's excellent Puglia: A Culinary Memoire calls for a stuffing of leeks, escarole, black olives, anchovies, capers and fresh tomato. She notes that in many parts of Puglia, the escarole is omitted, which is clearly the case in Grumo Appula. And some recipes call for adding an egg or two to the filling, which would, of course, give it a much firmer texture when baked.

There are various possible crusts for this pie. The classic crust, which Zia Angelina's (as well as Ferrante's) recipe calls for is made from a pizza-like dough of flour, oil, water and yeast. Some recipes call for adding a bit of white wine to the dough. In Zia Angelina's recipe, the dough is not allowed to rise before being rolled out, but in Ferrante's, it is. Maria Savino's recipe calls for a simple crust of flour and oil, with only a bit of water if needed to bind the ingredients and without yeast, known as sfoglia all'olio—a kind of Mediterranean pâte brisée. And, last but not least, Maria also uses packaged crust (she uses Pillsbury's brand), something which—not being much of a baker—I can heartily endorse as a perfectly acceptable shortcut.

Since onions are the 'star of the show', the choice of onion will strongly affect the end result. In Puglia, the most favored choices are cipolle rosse di Acquaviva delle Fonti, a very sweet red onion, or cipolle sponsali, a kind of a cross between green onion and leek—hence, I would surmise, Ferrante's suggestion of leeks for this dish. Maria Savino suggests using green onions (also called 'scallions' in certain places). Fresh onions, those sold in the spring with their green tops still on, would also work very nicely. And for those in North America, the sweet Vidalia onion—which I used when I made this—is a great choice as well. In a pinch, regular yellow onions will do, but the filling will not have the same sweetness which, combined with the savory elements of the filling, provide the typical character of the filling.

Although none of these recipes specify, it is also important, at least in my book, to slice the onions from top to bottom (ie, vertically) rather than horizontally, across the grain. This helps the onion slices to remain intact; they would otherwise complete melt during the fairly long cooking process they need to soften well. That will give your filling a pleasing bit of texture.

Although none of these recipes specify, it is also important, at least in my book, to slice the onions from top to bottom (ie, vertically) rather than horizontally, across the grain. This helps the onion slices to remain intact; they would otherwise complete melt during the fairly long cooking process they need to soften well. That will give your filling a pleasing bit of texture.

To see one of these other versions made, I would refer you to this excellent demonstration by my "Foodbuzz" friend, Nicoletta Tavella.

A final note: If you are interested in learning more about this dish, and perhaps Googling it, it should be mentioned that this dish goes by a good number of aliases. In pugliese dialect, it is called pizztidd or pizzutello. It can also be called scialcone di cipolla or pizza di cipolla. A bit confusing, but this kind of variety is not uncommon for well-known Italian dishes.

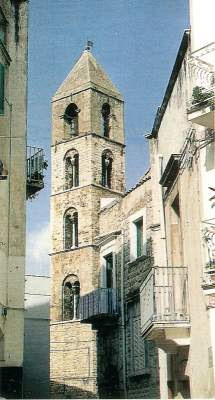

A view of Santa Maria Assunta, the 13th century 'mother church' of Grumo Appula.